Heard the one about the Northern Rail sandwich…? Thought not.

If you visit a busy mainline station anywhere in the United Kingdom, today’s concourses resemble a small town shopping centre. It is a far cry from an era when the only shops were those of W.H. Smith and Son, John Menzies, Finlays or Wymans. Other than newsagents’ shops, it was the buffet bar or restaurant. Till the start of rail privatisation, a parcels (Red Star) pick-up point and left luggage facilities were the norm at principal stations.

Modern day commentators comparing the retail offerings of Manchester Piccadilly in 1991 compared with 2016 would happy with the latter. More so with Piccadilly’s airy [2002] concourse being a favourable alternative to the 1960s building. Shop leases keep any of Major Stations’ property portfolio running smoothly. It is possible to have breakfast, lunch, dinner and supper at Piccadilly station. From retail and user-friendliness points of view, a success, which is why it’s in the Champions League of any of Network Rail’s customer satisfaction ratings.

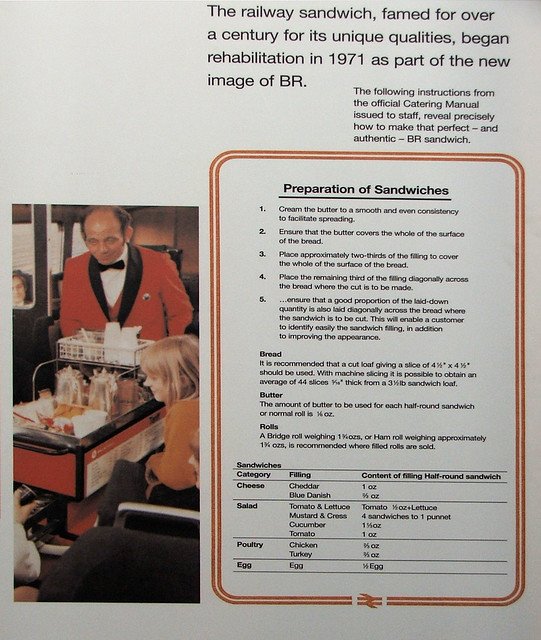

Though I consider myself in favour of publicly funded rail operations (return of British Rail, better trains in Northern England, etc), privatisation also succeeded in killing off the British Rail Sandwich Joke.

Yes, as heard ad nauseam on many a light entertainment programme or live production since 1948. Given that rail privatisation began on the 01 April 1994 (I remember the day well; I was milling about in Spindles Shopping Centre after boarding a recently privatised – and split – GM Buses 409 to Oldham), there’s an entire generation that hasn’t had the joy of a B.R Sandwich Joke. Therefore, if you’re under 22 years of age, I would ask your parents (otherwise, read on).

What’s yellow and white, and goes up and down at 30 mph?*

A common trope since rail nationalisation was the fact that British Railways’ sandwiches had curly crusts. They were often regarded as stale. The roots of this trope lies in the era of Brief Encounter and Ealing comedies rather than the latest Star Wars flick. It stems from a time when sandwiches were kept under a dish on a plate. Being out for quite a while, in spite of being made on the day and kept under cover, resulted in their curliness.

Then came cling film. Once again, freshly made sandwiches; this time, soggy rather than curly. In this case, any tomato or tuna based sandwich was best avoided. This proved to be a bit of a no-no whilst eating on the go.

Making the going cheesy

We have the second half of the 1960s to thank for the rebranding of British Railways and its facilities. Thanks to the Design Research Unit, British Rail’s famed double arrow symbol and its Rail Alphabet typeface made for a modern yet approachable image.

As well as a clean sans-serif typeface and a common identity across the network, great improvements were made on the hospitality side of things. Back in 1965, the British Railways Board, thanks to its inheritance from The Big Four companies and its predecessors, had one of Britain’s largest catering concerns.

One of its arms, British Transport Hotels, had a wealth of hotels in seaside locations and urban centres. They also ran station buffet bars and restaurants – a bit like the Trusthouse Forte of the permanent way. Through British Rail Catering within BTH control, this meant most of the station buffets, even on medium sized staffed stations; at the other end, Tourist Restaurants and bars at main termini.

In 1973, British Rail Catering’s division was spun off as Travellers’ Fare. Though catering revenues improved on station concourses, the same couldn’t have been said of its sandwiches. They continued to be the butt of jokes on most comedy programmes, especially on The Two Ronnies. One episode of End of Part One, in a spoof Top of the Pops style countdown asked “Why Are They Still Being Served?”

Throughout the late 1970s to early 1980s, the British Rail Sandwich Joke was the gift that kept on giving. It was clean enough for train enthusiasts from 6 to 86, and felt just at home on Crackerjack as much as The Young Ones.

All was not lost when B.R. called upon the services of Prue Leith. As faster trains meant fewer sit down meals on or off the train, this meant sandwiches could have been a popular option on the HST to Cornwall. With a wider variety of flavours, sandwich sales picked up. Health conscious passengers shunned bigger cooked lunches for lighter lunches.

Even so, there was changes under way. British Transport Hotels was privatised in 1983, shortly after Thatcher’s landslide victory. Travellers’ Fare retained its core market though some outlets were gradually privatised. 1986 saw Travellers’ Fare’s on-board catering transfer to InterCity – with this arm known as On Board Services.

Two years later, Travellers’ Fare was privatised, sold to their management. There was plenty of potential for a new set of British Rail Sandwich Jokes, but something else changed.

Goodbye from them…

With the threat of privatisation, the B.R. Sandwich Joke was due to follow suit. 1988 saw the end of The Two Ronnies. Light entertainment had changed thanks to the rise of alternative comedians and – in the words of the late Ted Rogers – “the Oxbridge lot taking over”. Perhaps curly crust ceased to get the woofers in 1988 as well as the advertisers.

Away from the cameras and spotlights, the Travellers’ Fare brand itself faded from view in 1997. There had been previous attempts to introduce other brands within its portfolio, most notably Casey Jones Burgers on mainline stations. There was also Quicksnack, whose undertakings were mainly kiosk sites on platforms. Come 1992, the business was sold to Compass Group, becoming Select Service Partner in 1997.

The loss of Travellers’ Fare from our stations came before the completion of British Rail’s privatisation in March 1997. 1993 saw the replacement of Casey Jones Burgers outlets with branches of Burger King. In their place would be Uppercrust, Ritazza, Pumpkin, and the like. The main station buffet at Manchester Piccadilly became a Little Chef. The arrival of NYNEX Arena saw The Dome becoming Manchester Victoria’s sole buffet.

Then the unthinkable happened. The railway sandwich lost its stigma. Curly crusts had long disappeared, cling film also followed suit. In came exquisite packaging in cardboard form prominently displaying the brand. By the 21st century, Uppercrust and Pumpkin units would also be seen in bus stations and coach stations. Ritazza would also be a coffee of choice in service stations and hospitals.

Today, it is possible to enjoy Starbucks coffee and other alternatives at our mainline stations (i.e: the superior Java at Manchester Victoria station), as well as SSP’s outlets and Burger King. Now, you could also get a quick ready meal, some fancy chocolates, something for the weekend from Boots, and a decent pint of real ale. Oh, and you can still nip to WHSmith for a newspaper or The Great British Train Times.

Though today’s mainline stations are also mini shopping centres, what of on-board catering?

The crumbling edge of on-board catering

The state of on-board catering on our rail network is a fragmented affair. Under British Rail, their breakfasts were popular with First Class commuters, but the sandwich stigma lingered. Probably because proletarian on-board catering meant the infamous sandwich and its other cousins, particularly weak tea and substandard pork pies.

Today, it is just as easy to nip to Uppercrust for a butty and a brew, so long as you can find a good table seat on the train. If you’ve a Greggs or Boots nearby, better still. Independently owned buffet bar? You’re laughing big style.

On Virgin inter-city services, the First Class menu has the usual breakfast options, plus a range of main meals and snacks. All of which served at your seat and included within the fare. For standard class passengers, hot food options lack the variety of British Rail’s operations; in the late 1970s, The Great British Breakfast was available to anyone who frequented the buffet car. Hot food on standard class, paninis, and bacon butties: a real step backwards.

The most common form of on-board food delivery to standard class passengers is the trolley service. One downside of this is its (lack of) effectiveness on crowded trains. Today’s Class 350s from Manchester Airport to Glasgow Central or Edinburgh Waverley lack – as well as the obvious dearth in capacity, even with 8 carriages – hot food. Which is woeful at best if you’re on a train for four hours. Compare and contrast with The European in the mid-1980s: air-conditioned Mark 2F carriages and a proper buffet car.

Though a buffet trolley may be adequate for Stalybridge to Scarborough or Hull, the true inter-city nature of the Anglo-Scottish expresses from Manchester stations demands proper buffet facilities. Eating on the train, whether a shop bought or home made sandwich, or cooked breakfast in First Class is a joy to behold.

Till recent times, regional express trains had a buffet trolley. Under First North Western’s franchise (1997 – 2004, late North Western Trains owned by Great Western Holdings), the Manchester Airport to Blackpool North, and Stockport to Llandudno express trains via Piccadilly had a Trolley Service. As to why they are a rare sight could be due to the following:

- Lack of profit on regional express trains;

- Overcrowding, thus inhibiting movement of buffet trolleys;

- Suitable options near local stations (i.e. Galloways’ bakery being opposite Wigan Wallgate station).

The last stated point is why, controversially, Southern ditched catering on all its commuter trains. What’s more, the price of sandwiches vary from franchise to franchise and open access operator, hence the following differences:

- Virgin East Coast: £2.95 (Egg and Cress);

- Grand Central Railway: £3.50 (any filling);

- South West Trains: £3.35 (Double Egg and Cress);

- Scotrail: any filling starting from £2.50;

- First Hull Trains: any filling starting from £2.90;

- Chiltern Railways: £2.95 (Egg and Cress);

- Arriva Trains Wales: £3.20 (Egg and Cress).

Before 1997, the sandwiches were just as expensive as they are today, but there was one clear difference. On the plus side, the same prices throughout most of the British Rail network regarding on-board catering. If any differences, within each BR sector (InterCity compared with Network Southeast and Provincial sectors). On the down side, the serial track basher or long distance commuter has countless prices to remember. Which is why it’s easier to admit defeat and nip to Greggs or Wetherspoons on arrival.

Before you ask, I prefer to make my own or call into Sainsburys for a meal deal. Or, better still, call in a local butty shop near the station (Chilli Tree near Stalybridge station springs to mind). It is, most of the time, a lot cheaper.

But, on the rare occasions I have called in to Uppercrust or bought food on board (some confection, TPE…), the experience is far removed from those of 1970s and 1980s comedy writers. The sandwiches don’t curl; the best pork pies are within the Northern Powerhouse’s hinterland on both sides of the Pennines. Tea on-board has improved, not least the joy of drinking Taylor’s of Harrogate’s finest en-route to Hull Paragon (better than Pumpkin’s offerings from the said station).

In conclusion, on-board catering is hit and miss on our trains. One welcome aspect is the use of locally sourced suppliers. The most retrograde step, is the lack of hot food options for standard class passengers.

As for British Rail Sandwich Jokes, the frequency of them in the 1980s could be due to British Rail’s attempts to modernise the network. Also the drafting in of Prue Leith and Clement Freud to improve their food offerings. The BR Sandwich was an easy target, yet they were enjoyed or endured in their millions. They were our soggy or curly sandwiches.

Most obviously, because’s there’s no British Rail, the joke is dead. Redundant. Sat in C.F. Booth awaiting the cutter’s torch. Rail privatisation, apart from perceptions of poor service, high fares and crap trains, has also been bad for end-of-the-pier comedians. Or writers of railway jokes. Between the lines, a lack of family comedy shows on television is another factor.

To be honest, I never cared for British Rail Sandwich Jokes in the first place. I always considered them to be stale and on the puerile side (Best Before: 16 May 1988 the last time I checked). As for the one about the Northern Rail sandwich, I still don’t know…

S.V., 14 January 2016.

* Postscript: The Lost Northern Rail Joke:

What’s yellow and white, and goes up and down at 30 mph?

An egg sandwich on a Pacer unit.

Wonderful and funny article! thank you it takes me back, as does the ‘The joys of watching TV at school in the 1980s and 1990sI’ would like to link your article on BR Sandwiches in a post on my website if that is ok with you?

LikeLiked by 1 person